A groundbreaking collaborative initiative between University of Cape Town (UCT), South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA), and Global Digital Heritage Afrika (GDHA) has revealed, with unprecedented clarity, the remnants of pre-colonial urban landscapes once inhabited by Basotho and Batswana communities in southern Africa.

At the heart of this project lies the power of the LidArc initiative, a US$10 million project that GDH is developing during the next 5 years all around the world. It aims to expand LiDAR access for heritage education and research, including data-sharing with descendant communities. GDH has also used the technology at global heritage sites such as Petra in Jordan and the tunnels beneath the pyramids of Guatemala.

Why LiDAR Matters

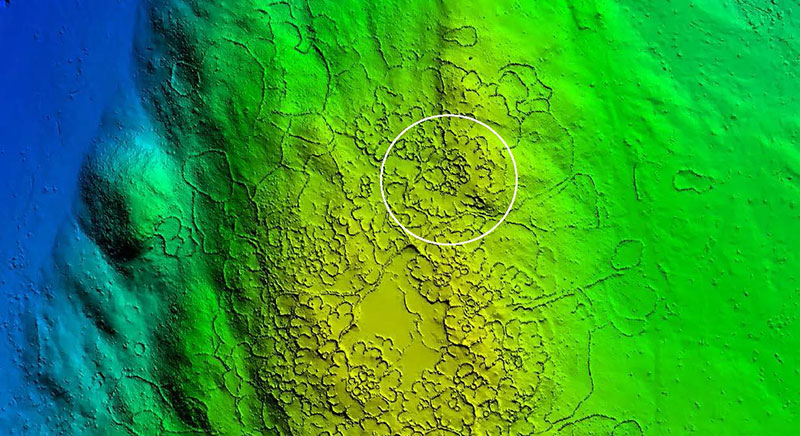

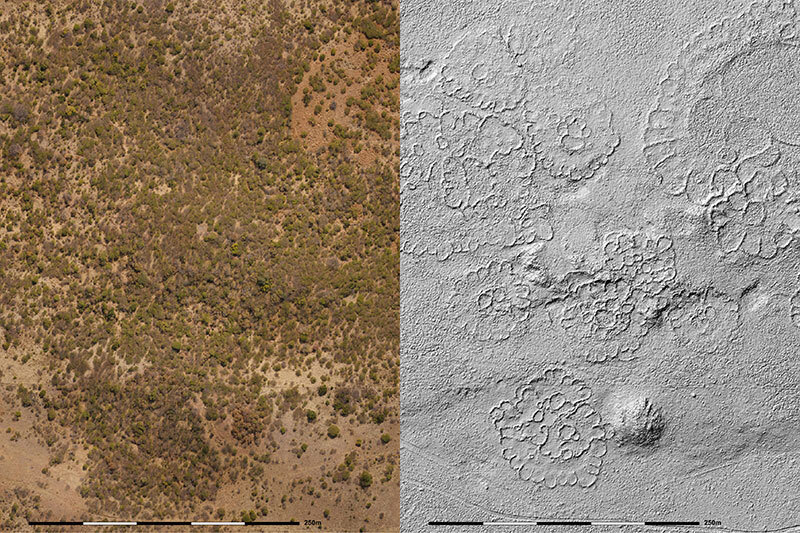

For decades, dozens — even hundreds — of Iron-Age stone-walled villages across what is now Gauteng, North West, Limpopo, Free State and Mpumalanga provinces were known only from fragmentary archaeological work and oral traditions. However, dense bush and overgrowth made comprehensive mapping impractical. LiDAR changes the game: it lets researchers “see through” vegetation, reconstruct settlement layouts, and visualize entire human landscapes at once.

In the initial survey alone (covering ≈ 26 km²), LiDAR imagery already revealed patterns invisible from satellite photos or on-the-ground survey — showing the true scale of the towns, their spatial organization, and even hints of social-economic structures centered around cattle and metallurgy.

What Are We Seeing — Rediscovering Ancestral Towns

Some of the sites under investigation include towns such as Molokwane and others, dated roughly between 1770 and 1830. Based on the LiDAR-derived layouts, archaeologists can now estimate population sizes — for example, Molokwane may have housed between 7,000 and 12,000 people.

Beyond simple population numbers, the new maps highlight complex aspects of social life: clusters of homesteads arranged around cattle enclosures, semi-circular back-courtyards, paths linking households, and the former expanse of what were once thriving villages.

More broadly, these towns were not isolated hamlets but components of a widespread settlement network across southern Africa. The ability to visualize tens of thousands of households across thousands of sites offers a transformative perspective on pre-colonial urbanization in the region.

Implications for Heritage, History, and Digital Archaeology

For heritage research and education, the LiDAR-driven reconstructions mark a paradigm shift. As UCT archaeologists note, we can now reinterpret social, economic, and political dynamics of 18th–19th century southern Africa — especially systems based on cattle economies, metallurgy, and trade — with far more precision.

For descendant communities, the mapping gives visibility and voice to ancestral landscapes long obscured by natural regrowth or modern development. As GDHA director and SAHRA representatives emphasize, this work is “not just about maps,” but about reclaiming ancestral heritage and making it accessible — digitally and publicly — for future generations.

From the perspective of digital heritage, the project is a clear example of how emerging technologies (LiDAR, 3D mapping, data sharing) can democratize the study of ancient societies — not only in globally famous regions like the Mediterranean or Mesoamerica, but also in Africa, where histories have long been undervalued or under-studied.

What’s Next

The initial LiDAR coverage — though revealing — covers only a fraction of the region’s former settlement zones. The team behind UCT, SAHRA and GDHA aims to expand the mapping over the coming years, with an investment of tens of millions of dollars to broaden LiDAR access for heritage research and education.

As this unfolds, the integration of LiDAR data with on-the-ground archaeology, oral histories, and community engagement promises a richer, more inclusive reconstruction of southern Africa’s past — one where long-lost towns and communities are re-imagined, their stories told, and their legacy preserved.